Understanding The Prompter: Lessons from Bonfiglio

Understanding The Prompter: Lessons from Bonfiglio

In Race and the Rise of Standard American, Thomas Bonfiglio argues that famous American figures like Noah Webster played an influential role in standardizing American English. According to Bonfiglio, “The ideologies and receptions of such influential figures are not only symptoms, but also determiners of the national consciousness of pronunciation as it relates to race, class, and power” (Bonfiglio 2002:6). Figures like Webster used language to reflect their ideologies about race, class, and power. Webster, however, was writing in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, before by increased immigration to the US escalated racial and ethnic xenophobia. Instead, Webster focused on class differences. Bonfiglio, recognizing this, acknowledges that American authors like Webster, who were writing about language before the mid-19thcentury, used language to rearticulate class (rather than racial) differences (Bonfiglio 2002:228). While Bonfiglio writes specifically about the way class and racial differences are rearticulated using locution, Webster adds another strategy, also applying labels and descriptions like "The Under-Lip" to emphasize differences both within and between classes.

Webster’s preoccupation with class is demonstrated by his focus on economic prosperity and high-class status. His emphasis on wealth is first embodied on the title page, which states his inclusion of Benjamin Franklin’s essay, The Way to Wealth, demonstrating the value Webster places on achieving wealth. After beginning his book with the topic of wealth on his title page, Webster concludes his book with the same principle, writing that he is “sincerely wishing his readers virtue, health, and dollars” (Webster 1808). This closing statement is directly followed by Franklin’s The Way to Wealth. By emphasizing “wealth” and “dollars” at the beginning and end of his book, Webster establishes economic prosperity as a major value, which he assumes his readers hold as well.

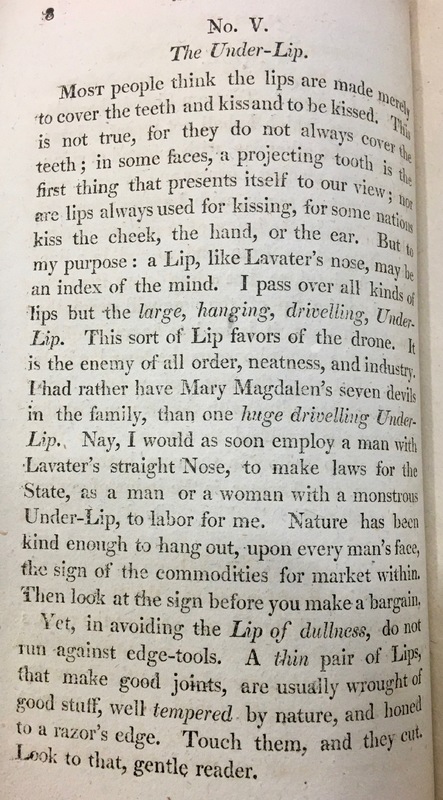

In the passage The Under-Lip, Webster continues emphasizing the importance of wealth and labor (associated with class) as ways of differentiating between types of people, using the under-lip, as a sign of a person’s ability to gain wealth.

While Bonfiglio claims that language rearticulates class, race, and power differences using the connotations of certain pronunciations, Webster relies more heavily on labels and descriptions. Bonfiglio writes that “when a certain locution becomes stigmatized and avoided by a given group, it is because of the associations and connotations of that locution” (Bonfiglio 2002:14). Meanwhile, rather than avoiding a certain pronunciation, Webster suggests that an entire type of person – those with under-lips – should be avoided (Webster 1808: 8). As this exhibit’s section about the under-lip explains, Webster associates the under-lip with incompetent laborers. In doing so, Webster also implicates the body (in this case, the lips) as a measure of a person’s worth. Like racism, in which phenotypical differences including skin color are used to measure a person’s worth, “The Under-Lip” demonstrates Webster’s judgement of a person’s competence based on lip-type, which he then labels with the phrase “the under-lip.” By promoting the label “under-lip” and using a biological difference to measure worth, Webster extends Bonfiglio’s theory that locutions re-inscribes differences, to show how labels re-inscribe difference as well.

The Prompter demonstrates the way influential American figures like Noah Webster reacted to and re-inscribed class differences as they standardized American English. Because The Prompter defines and explains common phrases rather than teaching pronunciations for those phrases, there is no point in which pronunciations re-inscribe differences. Instead, in The Prompter, Webster uses labels and descriptions to re-inscribe differences.